AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

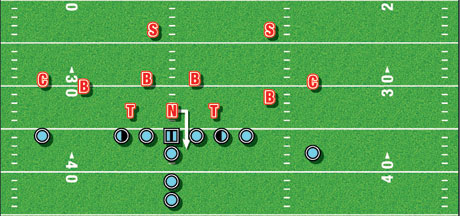

Nose Guard: Establishing an Effective Two-Gapby: Mike KucharSenior Writer, American Football Monthly © More from this issue As we all know, football schemes are cyclical. Trends seem to re-surface. The double wing has become the spread, the Wing T has morphed into elements of the fly sweep and the old sixty defense has transformed into a 4-2-5. While the schemes may come and go, one position has been as constant a cornerstone in defensive football as the name that it bears- the nose guard position. Usually, this denotes images of Ted Washington from the Buffalo Bills or Gilbert Brown of the Green Bay Packers stuffing up the middle of the offense with their 300 lb. girth. But like anything else, the true double-gap nose technique has shifted more into the evolution of shade defenders who have only one gap to be responsible for. Thanks to Jimmy Johnson and the development of even fronts, teams have started to employ more tilted nose players whose main objective is to get off the ball and get penetration into the backfield, rather than occupy two points of attack on the offense. Even the teams that are running some odd fronts like the 3-3-5 or 3-4 schemes usually have their nose slant or angle into a gap in order to avoid the responsibility of playing both. Chances are if you search far and wide enough, you could still find some programs that incorporate a two-gap nose technique and have had some success in doing so. For those who want to learn how to develop a player into one that can be successful in a two-gap scheme, what these coaches have to offer may shed some light on a lost technique. Personnel So the Teddy Washingtons and the Gilbert Browns types may not be resurfacing anytime soon – chances are those players are working on the other side of the ball these days. But the fact of the matter is you don’t need a 300+ lb. player to anchor your defense. “I always thought that a quicker, more agile type of player has been more productive in that spot in my experience,” says Denny Marcin, who has spent over 50 years of coaching at the high school, collegiate and professional levels, most recently with the New York Jets. “They just need to have good upper body strength to be able to control the center. Quickness is always more important than speed. He needs strength in pressing the line of scrimmage and keeping the center off the linebackers.” According to Eric Mathies, the defensive line coach at Western Kentucky, teams are shifting more to a stunting style nose because finding a pure two-gap technique is hard to come by. “It’s so hard to find that kid. It’s a lot easier to find a smaller guy who can shoot gaps,” said Mathies, whose Hilltoppers run a 3-4 scheme. “We don’t really major in the two gap but we do enough of it to change things up. It all depends on the kid that you have. In the past we’ve found guys who can do that and control two gaps and we’ve had some success with it.” So what is the ideal size for your protypical two-gap nose technique? Mathies believes that guy needs to be in the 6-1 to 6-3 range and weigh from 270-300 pounds. “Anything bigger than that and he’s going to the other side. We need guys that can move.” Another defensive line coach, Mike Fenoga at the University of New Mexico sincerely agrees. “You’re really looking for a guy in the 275-280 pound range who can go,” says Fenoga, who helps DC Joe Lee Dunn run his odd stack scheme for the Aggies. “That kid has to hold onto the center so he has to be strong. The most important thing is leverage, and getting underneath him – especially if you’re playing two gaps. It’s as simple as pad under pad.” Technique Whether the opinions on personnel types may change, when it comes to technique most D-line coaches feel everything starts with the hands and feet. “The first thing is always the hands,” says Mathies. “The center moves so much from right to left – especially today with all the zone schemes out there – it’s vital that we get the nose guard’s hands on the frame of the body right now. A nose still has the responsibility of not letting anyone up to the linebackers. He has to fight that center as hard as he can to prevent it.” Fenoga agrees in the same principle of getting hands inside the frame, or as he call it the “steering wheel.” But before you learn how to operate the steering wheel, you need to put your foot on the gas pedal. That comes with moving your feet, which starts with the stance. “We talk about getting a 70-30 ratio in our stance with the majority of our weight back,” said Mathies. “That’s how you get your hands on quickly. If you’re weight is distributed more towards your front end, it’s much tougher to make inside contact on the breastplate. I never understood teams that line their nose up in a four point stance because it doesn’t allow you to get your hands on him right away.” Mathies will actually emphasize this on a five-man sled by having his players hold the feet of the ones getting the reps so that they are unable to move. “They are forced to unlock their hips and shoot the hands. It just emphasizes hand movement.” Most of the schemes that defenses see now are zone schemes, which may be part of the reason why many teams don’t employ a two-gap nose anymore. Since zone schemes rely on more of a stretch blocking scheme by the offensive line, in order for the nose to be involved in the play, he must be able to control the line of scrimmage. “Even though we’re two-gapping, the man in front of us is always our key,” says Fenoga. “Basically we strive to get good extension and good separation on the snap. We have to pound our feet laterally if the ball goes away. He mirrors that center. He needs to see hat level. If we start to see flow the nose is always responsible for the backside A gap. He’s almost like a backside linebacker because he is always responsible for the backside. He must have cutback so the linebacker could come over the top and flow. We want to stay back while those linebackers are flying to the football.” In order to change things up, Fenoga and Mathies will both employ some sort of slant or angle scheme (See Diagram 1). The nose will start in a head up shade and on the snap execute a “Rac” (rip across center) move therefore declaring which A gap he is responsible for while the linebacker handles the one opposite. “We’ll open up to three o’clock if we’re going right and nine o’clock if we’re going left by taking a lateral step to the outside pad of the center,” said Mathies. “We want to get in that gap and run right away. There is really no reading involved.”

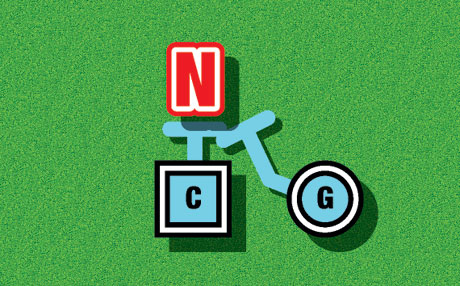

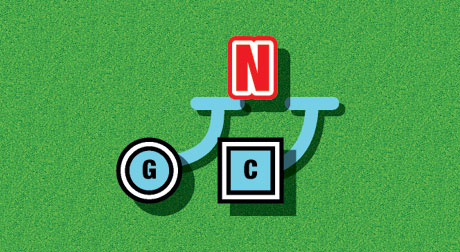

Fenoga employs the same scheme which he calls a slant and angle. He’ll even stem his front from a 3-3-5 defense to an over or under scheme to give the illusion of a four man front. “You have to be able to give different looks,” says Fenoga. “You can move into a 3-4 or a 4-3 at will. Stemming confuses the offensive line and is a good mixer for the run stopper. As long as you keep it simple for your kids and fit it to your personnel you can do anything you like.” Drill Work Because the majority of schemes that Western Kentucky sees are zone schemes, there are two main blocking schemes that Mathies works on during the week in what he calls his key read drill. The first scheme is a double team (See Diagram 2) used on the inside zone play. The nose will line up head-up on the center while Mathies stands behind instructing the guard and center to execute a double team block. When his nose gets this read, Mathies instructs him to drop to a knee and try to fit inside the gap he’s responsible for. “It’s one of the things I got from Greg Mattison, now at Florida, when he was at Notre Dame. He’ll feel the pressure of the post-man, or the center that he’s lined up on. It’s important that the nose drops the leg where he’s getting pressure from so he can stay in his gap. If he drops his other leg he can move into an adjacent gap.” The scheme that Mathies will utilize in his key read drill is the scoop scheme (See Diagram 3) most commonly employed on stretch or outside zone plays. Here the center will work in conjunction with the guard to overtake the nose. It is a fundamental principle that the nose cannot let the backside guard take him over, thus lose his gap. “We teach our nose that if the pressure is inside and not directly on top of him, it is a scoop scheme. We talk to them about blowing the doors open by exploding with the play side hand and flexing the elbow out. This prevents the center from getting off of the nose and getting hooked up on the linebacker. By throwing your elbows out, it allows you to open your hips to that gap. It’s a game of inches and our players need to realize that they can’t let that center off of them. It’s the worst thing they can do. They need to help the backer out and not get cutoff at the same time.”

|

|

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2024, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved