Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

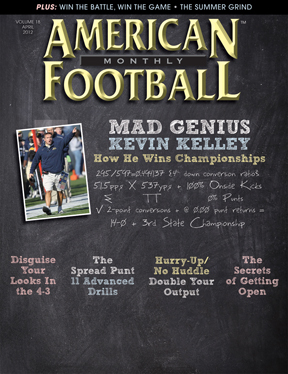

Mad Genius - Kevin Kelley’s unorthodox approach may break all the ‘rules’ but it sure produces results.by: David Purdum© More from this issue A job interview with Pulaski Academy (AR) head coach Kevin Kelley is a little different. He begins by talking about loyalty and what it means to be an assistant coach. Then, he cuts to the chase. “Hey, we’re into some weird stuff,” he tells inquiring coaches. Weird and very successful. Kelley started getting weird in 2007. He stopped punting. But that was only the beginning of wholesale philosophy changes that have transformed the Bruins into an Arkansas powerhouse and have intrigued coaches from all levels of football. Pulaski Academy is 49-7 and has won two state championships over the last four seasons, including this past season’s undefeated march to Kelley’s third state title. During the four-year run, Kelley has punted four times, rarely returned a punt and has attempted an onside kick more often than not. He also goes for two-point conversions over 50% of the time. Kelley has gone for it on fourth and 22 from his own 20. In the 2010 state championship game, he went for it on fourth and 10 from his own 10. “We didn’t get it, but I was OK with that,” he said. Prior to becoming head coach, he watched a video by a Harvard professor that had analyzed every game from college football for three years. In that study, it revealed that if a team takes possession inside their opponent’s 10-yard line, they have a 92% chance of scoring. If they take possession say after a punt between their opponent’s 30 and 40 yard line, they will score 77% of the time. Kelley argues that by not punting, the opposition has just a 15% more chance of scoring. The numbers he feels tells him to go for it. “Punting is offensive failure. It’s willingly giving the ball back to the other team. If we average just 50% on fourth down conversions, then we are keeping the ball half the time that playing conventional football would have us give up on a punt. And for what, 30 yards of field position?” The numbers are somewhat more straightforward when it comes to onside kicks. “We took three years of data from when we kicked deep and occasionally kicked onsides,” said Kelley. “Kicking it deep gave the ball to our opponents on average at their 33-yard line. Onside kicks gave them the ball at their 47 yard line. So we’re giving up 14 yards of field position for a chance at getting the ball which basically amounts to a turnover.” In November, the Bruins made national news by taking a 29-0 lead without allowing their opponent, Cabot High School, to touch the ball. First, Pulaski recovered an opening onside kick by Cabot and scored. The Bruins then recovered their own onside kick and scored on the next three possessions. Before Cabot managed to snag one of Kelley’s 12 different versions of onside kicks, they were down four touchdowns. Kelley also never returns a punt. Never. “Usually the average gain on a punt return is 6-7 yards,” said Kelley. But there are many factors that can lead to a turnover or negative yardage. There’s obviously the possibility of your returner fumbling the ball, the potential of a penalty of blocking in the back, and possibility of roughing the punter.” For all those reasons, Pulaski Academy doesn’t have anyone back to field a punt. “We also line-up in a defensive formation and do not rush the punter so there’s no chance of a roughing call,” explained Kelley. “By doing this, we accomplish what we want to do – a guarantee that we’ll get the ball back. We also spend zero time on practicing punt returns which gives us more time to spend on other things.” Pulaski also converted on 15 of 20 two-point conversions in last year’s championship run. Making one has a psychological advantage. “What you try to do is make one early and force the opposing team to attempt one. They usually aren’t prepared as much so if they don’t make it and you score again, all of a sudden you’re up two scores. We only need to convert 50% of two-point conversions to be successful.” Call it what you want, but there’s a method to this madness that is much deeper than Xs and Os and field position. It stems from the value of possession of the football, something that Kelley believes is vastly underestimated by coaches. “Look at the number of touchdowns scored on defense as opposed to the number scored on offense,” Kelley said. “Now, you obviously score more on offense. So we are not going to give you back the ball until the rules state we have to.” “We found that teams score on a much higher percentage when they acquire the ball by a turnover,” Kelley explained. “If you get the ball after a kickoff, usually the other team has scored and your team is a little down. In that situation, you score at a certain rate on that drive. But if you get the ball at the same point on the field after you have intercepted or recovered a fumble, you score at a much higher rate. We started looking at our numbers and the same things occur with us. After we convert on fourth down on a drive, we score at a much higher percentage.” The same thing happens after recovering an onside kick. A team that just got scored on then fails to recover an onside kick is demoralized, said Kelley. “Not only that, but when a team does recover an onside kick, they’re not overly excited, because they just gave up a touchdown,” said Kelley, who is an avid reader of books on psychology. “The emotional swing isn’t that great, so it’s a win-win for you in that respect. Plus, the amount of field position you give up isn’t that much.” Special teams coach Adam DePriest has a dozen onside kicks in his repertoire. He uses different formations with motion and shifting, while keeping a close eye on how the opponent adjusts. The wide variety of formations and schemes forces an opponent to spend time preparing for onside kicks instead of offense and defense. And there are some unique onside kicks. For instance, on “Copter,” the ball is laid flat on the ground. The kicker attempts to toe kick the nose of the ball, causing it to spin like a propeller as it travels the required 10 yards. “It’ll go 10 yards then it’ll kind of curve back to you almost like a boomerang,” said DePriest. “It’s got so much spin that it’s tough to field.” The Bruins opened the 2008 state semifinals with “Copter,” and recovered it to jumpstart a 54-24 win over Greenwood. The most important element of a successful onside kick is the kick itself, emphasized DePriest. But he also believes choosing the right personnel for your kickoff unit is crucial. “You have to have guys who aren’t afraid to hit, and the little scrappy guys who just want to go get the football,” DePriest said. “We had a kid that was maybe 5-foot-6. He wouldn’t have seen the field otherwise, but for some reason, he had a nose for the football. You need a good mix of hitters and guys who know how to come up with the football.” It’s easy to let the lack of punting and abundance of onside kicks overshadow what is a very potent Bruins offense that has averaged more than 520 yards per game since 2008. In 2011’s championship run, the Bruins ran every play out of shotgun, mixing in a zone running game with a versatile passing game. They had approximately a 55/45 pass-to-run ratio. They vary the tempo, speeding up when catching a defense in a bad match-up. Kelley hand-signals in the play from the sideline; the quarterback has only one audible. The assistants in the press box are responsible for noting the leverages and depth of the safeties and corners. Kelley wants to know where the safeties line up if the ball is on the right hash or the left and according to formation. He runs 10 different formations on the first 10 plays of the game. There are not timing routes in the passing game. The route design is focused on sight adjustments. It’s the receivers’ job to get a line of sight with the quarterback, who is not allowed to throw a pass without eye-to-eye contact. “We use hips and shoulders against the defense,” Kelley said. “For example, if someone wants to play us man-to-man and we run an out rout, it might be five yards if the defender turns and opens his hips, we’ll break at five yards. Or if he’s in his backpedal or is running with us, we’ll go to 10 yards or it might be 12 yards.” Against zones, Kelley preaches spacing by adjusting the depth of the routes. “Our receivers really know how far apart they have to play and work their routes,” he said. “We give them a lot flexibility to adjust their route based on what the defender is doing. “Let’s say we line up in a no-back situation and we’re in a 3-by-2 set and run all curls,” Kelley continued. “As we release off the line, instead of running vertically up the field for 12 yards and turning around in curl position, our guys as soon as they fire off, they’re looking at the defender they’re working on with another receiver. We try to put two guys in one guy’s zone – if the defender slides their direction, they’ll veer their rout out off the first three steps; or if he jumps to the inside, they’ll push in really hard. They’ll end up five yards left or right from where they originally began.” Kelley uses a double-post pattern out of the same 3-by-2 set, as another example. “We’ll run a double-post combo using our two inside receivers,” he said. “We can run it horizontally, which means you run one guy hard inside at the safety and the other guy on almost a vertical rout outside that safety. Or you can run one guy hard underneath the safety and the other guy runs a deep post behind that safety. “If I’m running a vertical double post, my underneath guy knows his first job is to get line of sight with the quarterback,” Kelley added. “He may run five yards or may run a 12-yard pattern. If the safety steps forward, then he will cut that post off hard. Then, the guy running the deep post will keep running vertically as long as the safety goes with him.” While punting is offensive failure, giving up an 18-play scoring drive is defensive failure, Kelley said. The Bruins’ defense is ultra-aggressive and blitzes more than 90 percent of the time. They base out of a 3-4, but much like their offense, will show a wide variety of looks, including four-and five-man fronts. “We don’t want to be a bend-but-not break,” Kelley said. “We either want to break them or get broken. Obviously, we want to stop the other team from scoring, but really we want to make something happen.” “A lot of guys talk about doing it, but only a few are really willing to do it,” said Kelley. “I got an email today that said, ‘Coach, I’m going with it. I’m going to do it, unless I chicken out.’” Kelley once had an offensive coordinator of a BCS school show up on a recruiting trip. But when they went into his office, the visiting coach didn’t want to talk about his players. He wanted to know about Kelley’s philosophy. “We talked and I laid it all out for him,” Kelley remembered. “He took it all back to his head coach but ultimately didn’t get as much done as he wanted. The guy ended up getting a head coaching job at another school. I looked at his numbers the other day and did not see a big change. I think the head coaching thing got to him a little bit.” Despite the naysayers, Kelley is convinced he’s not the one being risky. He knows the numbers are on his side and has three state championships to back him up. “The numbers say I’m not the one gambling; it’s the guys who aren’t going for it on fourth down that are taking the risk,” he said. “But it’s a lot like Columbus. When he set sail, people thought he was going to fall off the end of the world. If my philosophy is ever going to become more common in football, a lot of people are going to have to change their thinking. But, honestly, I hope they don’t, because it gives us an advantage.” Endless Onside Kicks Coach Kevin Kelley has an arsenal of onside kicks. Many include various formations with a different number of players on each side of the kicker. Some include moving the ball to different hash marks and motioning a player before the kick itself.

|

|

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2024, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved