Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

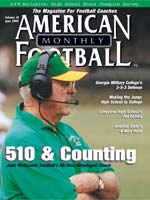

Making the JumpThree high school coaches that made the move to college assistantsby: Patrick Finley © More from this issue You ask Tommy Knotts why he decided to leave his job as head coach

of one of the most dominant high school programs in America for

an assistant’s job at a college football program. You wonder

how he could leave Independence High School in Charlotte, N.C.,

where his teams have won 62-straight games, the second-best mark

in the country.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved