AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

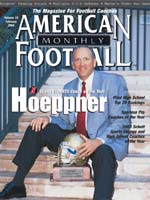

Leading the ChargeMiami of Ohio's Terry Hoeppner takes command of the college coaching landscapeby: Richard Scott © More from this issue Every college football head coaching job is tough in its own way. Every job presents its own trials, its own pressures. For Miami (Ohio) coach Terry Hoeppner, some of the most unique and heavy challenges in the history of college football surround him and try to stare him down every day. Every college football head coach has an office, too. None of them are like Hoeppner’s office complex. His place of work is more like a museum, a monument to the greatness that is Miami’s “Cradle of Coaches,” with pictures of former Miami coaches Sid Gillman, Woody Hayes, Bo Schembechler, Ara Parseghian, John Pont and Bill Mallory constantly looking over Hoeppner’s shoulder. Hoeppner always figured he knew what it was all about until he actually moved into t....The full article can only be seen by subscribers. Subscribe today!

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved