AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

|

|

Article Categories

|

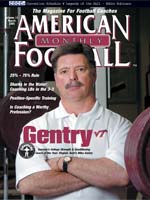

Heavy ImpactStrength and conditioning coaches and facilities have taken the game of football to a whole new level by: Jeff Davis© More from this issue

|

It’s the youngest, and

certainly in many respects, the most important element in developing

winning athletic programs, especially football, other than the head

coach himself. The strength and conditioning coach and his staff

can be difference makers between a winning program and mediocrity.

Before the early 1960s, only a handful of athletes dared to try

weight lifting. “They used to think you’d become muscle-bound,”

says Mike Burgener, for decades, the esteemed strength and conditioning

coach at Rancho Buena Vista High School near San Diego.

That old saw still held true for Burgener when he was a high....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

Subscribe today!

|

|

|

NOT A SUBSCRIBER?

Subscribe

now to start receiving our monthly magazine PLUS get INSTANT

unlimited access to over 4000 pages of 100 percent football coaching

information, ONLY available at AmericanFootballMonthly.com!

|

|

|

HOME

|

MAGAZINE

|

SUBSCRIBE

|

ONLINE COLUMNISTS

|

COACHING VIDEOS

|

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved

|