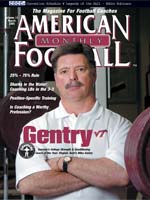

AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

|

|

Article Categories

|

A Part of the Master PlanThe Falcon\'s Al Miller has become a heavyweight among the NFL\'s elite strength and conditioning coaches by: David Purdum© More from this issue

The voice on the phone

said it was Linda Knowles, Bear Bryant’s secretary, but Al

Miller knew better. Growing up just 40 miles from Bryant, Miller,

a coach himself, had fallen for the ‘Bear Bryant’s on

the phone’ gag before.

“OK, yeah, sure,” he sarcastically replied to the imposter

secretary.

Then, suddenly there was another voice on the phone. “Boy,

when he got on that phone, there was no denying whose voice that

was,” Miller remembered with a chuckle. “I set up in that

chair and took notice right quick.” With only two years of

experience under his belt, Miller became Bryant’s last str....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

Subscribe today!

|

|

|

NOT A SUBSCRIBER?

Subscribe

now to start receiving our monthly magazine PLUS get INSTANT

unlimited access to over 4000 pages of 100 percent football coaching

information, ONLY available at AmericanFootballMonthly.com!

|

|

|

HOME

|

MAGAZINE

|

SUBSCRIBE

|

ONLINE COLUMNISTS

|

COACHING VIDEOS

|

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved

|