AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

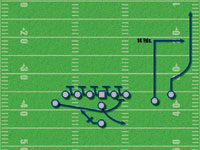

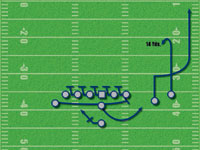

The Pistol Offense - Part IIThe Pass Gameby: Mike Kuchar © More from this issue Last month, American Football Monthly showcased the run game of the Pistol offense, the first of two installments profiling the versatility of the University of Nevada’s prolific offensive scheme. This month, we take an in depth look at the complementary play action pass game the Wolf Pack uses as a change-up when teams start to load eight or nine in the box to stop the run. Strategy of the Pass Game These days, most college football teams are figuring out a way to get their best players in space, while spreading defenses out. Nevada is no different. Head coach Chris Ault developed the Pistol offense in 2004 as a way to level the playing field by getting one-on-one matchups with receivers on the perimeter and having his undersized offensive linemen block people in space. While the foundation of the run game is being able to mix the inside zone (slice) play and the outside zone (stretch) out of different formations, the backbone of the Pistol pass offense is running the play action off both of those plays. The equalizer in the Pistol scheme is the alignment of the quarterback and the tailback. With the tailback being directly behind the QB, it provides instant deception to the defense – particularly for the linebackers who are trained to key the tailback. In fact, the popularity of the zone read play has changed LB’s reads to keying the offensive tackle to the side of the back. But in the Pistol, often times those LB’s can’t see the back because their sight is distracted by the motion of the quarterback. “It’s a lot easier to run play action out of the Pistol because of where the back is,” says offensive coordinator Chris Klenakis. “Nowadays because of the zone read, when you’re in a traditional Shotgun alignment you will always have a backside end who is taught to never close on that tackle’s down block. So it makes running naked plays at him very difficult. With the Pistol, you don’t get that problem. Especially if you’re giving a good dose of inside and outside zone schemes.” While over eighty percent of the success of the Wolf Pack pass game relies on setting up the run, Klenakis is not afraid to pull the trigger on early downs. “There’s nothing wrong with calling a first down play action pass game scheme, especially when you’ve been running the ball effectively,” says Klenakis. “I like the play action stuff best on second and medium because it’s a give or take down.” The majority of Nevada’s offensive formations are run out of 11 personnel – one tight end, one running back and three wide receivers. However, the great disguise is how many different formations Nevada could come out in utilizing the same personnel. Klenakis has over thirty different formations in his playbook using 11 personnel, which obviously makes it difficult for defenses to match up with them. The Play Action Nevada’s most productive play since installing the Pistol has been the slice play which is the inside zone play to the tight end side that American Football Monthly profiled last issue. So it makes sense that the Wolf Pack’s number one play action scheme is the Zone Pass Boot. The Zone Pass Boot is a naked play action scheme, meaning the QB – after making the run-action fake – gets out on the opposite perimeter with no lead blocker. The offensive line’s main responsibility is to ‘sell’ the inside zone. Klenakis preaches low hat/low pad level in order to deceive the second level defensive players who often read helmet leverage on the snap. While the line zone blocks away from the direction of the play, the wingback ‘slices’ across the formation to block the backside C gap, just like he would on the inside zone run play. “Except this time the wing will take somewhat of a different path, aiming for the outside hip of that backside end. Sometimes we’ll have him log the end, so the QB can get around or we’ll release him to the flat right away,” says Klenakis. “It’s a great goal line play. It depends how aggressive that player is. If he’s up the field often, we’ll get the wing to the flat right away. If he slow plays it, we’ll log him.” After the QB opens, just as he would on the slice run play giving the ball fake to the tailback who is downhill immediately, he carries the fake for two more steps past the handoff, pivots and works around the opposite end with the ball on his hip. “He should anticipate that backside end being in his face immediately, particularly if the wingback releases to the flat. It is a two-man route with those two backside receivers. Our most common route if we’re getting some form of cover three is running number one on a takeoff to get the corner out of the area. We would then have the slot break on a 14-yard out against the flat defender, usually a LB and a mismatch (See Diagram 1). Another option is running number one on a curl at 14 yards and number two on a wheel route. Either way the QB looks high to low on his delivery (See Diagram 2).”

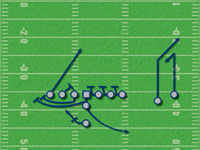

According to Klenakis, another productive play action scheme is the companion to the Horn Run play that the Wolf Pack uses as a change-up to the slice. In the Horn Run play, both the center and frontside guard pull, giving the defense some sort of counter read. In order to keep the element of deception, the Horn Pass will look exactly the same. Also a naked play action pass, the Horn Pass relies on that double pull to get those linebackers moving downhill, opening up a hole in the middle of the field. The tight end then exploits by running a route down the middle of the field. “He blocks down to sell the run for a two count then releases,” says Klenakis. “We just tell him to run deep over the football down the middle of the field. In theory, the line is used as a decoy. But they can’t get passive with their technique. They still must sell the run.” Klenakis likes to run the Horn Pass out of a double tight end set so you’re overloading one side with a trips formation. “What most teams start to do is play some sort of quarter or halves coverage to that three receiver side, so we’ll have the number one receiver run a hitch, while the inside slot runs a post-corner (See Diagram 3). You really put that corner in a bind. If he sits on the hitch, you take the corner. If he continues to get depth, zing the hitch for a few yards.”

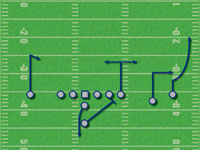

The Quick Game In order to provide a spark to the pass game, Klenakis does draw from a three step package in the Pistol. When he does, it’s usually the Y Option route. It’s a four man route with the focus predominantly on the release of the tight end. Keeping the 11 personnel intact, Klenakis’s favorite formation to run this is out of the tight/trips set (See Diagram 4). The offensive line slide protects with the tailback filling for the releasing tight end. To the trips side, the Z receiver will run a clear out route, with the slot receiver on a 14-yard out route and the tight end on an option route – one that can break outside or inside. The single receiver away from the play can run either a hitch, fade, or slant depending on the pre-determined call.

“Our QB’s pre-snap read is that single receiver. We’ll try to isolate our best guy. If we feel we have a mismatch, we’ll tell our QB to go to him right away and let him make a play. We’ll take that until they take it away” says Klenakis. “Once they start to roll to the single receiver side, we’ll look opposite. The tight end is going to attack the inside shoulder of the flat defender. If he floats to the out route by the slot, we’ll hook up with the tight end right away. If we see the defender sitting there, we’ll then go to the out route by the slot and, hopefully, the clear out by the Z would leave us with some running room out there.” Usually the progression for the QB is to read the safeties’ pre-snap. One high safety denotes cover three or cover one, so the first read would be the single WR side on a one on one matchup. If there are two deep safeties, denoting some type of quarters or halves coverage, going to the trips side would make more sense. “Either way it’s a universal route,” says Klenakis. “You’re never a play behind with this play. It’s a crucial go-to play in passing situations.” |

|

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved