Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

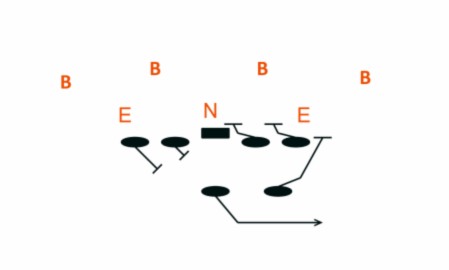

Sprint Out! One of the keys for a successful sprint out passing game is protecting the backside of your quarterback.by: Matt Franzen, Head Coach and Offensive Line Coach and Grant MollringOffensive Coordinator and Quarterbacks Coach, Doane College © More from this issue We divide our passing game into three different categories – 3-step, 5-step, and roll-out. As we operate from the shotgun formation about 90% of the time, we’ve made obvious footwork adjustments from the traditional quarterback drops that are used when working under center. This is our roll-out package, including our blocking scheme, quarterback mechanics and reads, and the route combinations that we use within this scheme.

Di....The full article can only be seen by subscribers. |

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved