AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

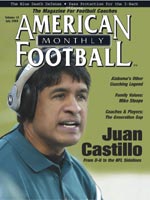

An Eagle Among UsBy going from sleeping in his car to manning the NFL sidelines, Juan Castillo has proven that a strong work ethic can pay off.by: Richard Scott © More from this issue At what point do the perceptions disappear and give way to reality? At what point do people in the football business, as well as the media and the fans, stop looking at the outside, at the skin color, at the last name, at the perception that his place in the world must be the result of a handout, a favor or a quota? What would it take to change the assumptions and move on to the facts? Would a man have to grow up in a small Texas town as the son of immigrants who spoke no English? Would he have to lose his father at age six and be raised by a mother who worked two jobs to make ends meet? Would a man have to walk on to a Division II football program and go on to play pro football? Would he have to work as an assistant for 12 years in ....The full article can only be seen by subscribers. Subscribe today!

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved