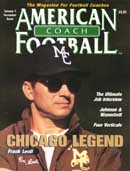

AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

Why They ReturnWhen coaches leave, their love for the game doesn't.by: Gene Frenette Florida Times-Union © More from this issue George Seifert had what seemed like the perfect life. He did what he wanted when he wanted to do it, a leisurely existence that he earned as a retired football coach with the highest winning percentage in NFL history. Following the 1996 season, he left his beloved San Francisco 49ers — the team that once played home games at Kezar Stadium where he served as an usher in high school — after 17 years and embarked on a lifestyle that qualified him for a Robin Leach profile. Having won two Super Bowl rings during eight seasons as head coach, Seifert decided to kick back. He traveled around the world with his wife, Linda, making stops in places such as Italy, New Zealand, Costa Rica and Chile. There were multiple getaways to Mexico. He went big-game hunting in the Rocky Mountains. And closer to his se....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved