Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

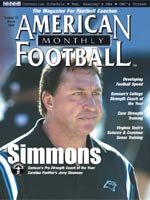

Science & Common SenseDeveloping strength and conditioning training for footballDirector of Strength & Conditioning, Virginia Tech © More from this issue Systematic resistance training and conditioning has become accepted

as a precursor to increased athletic success and an important component

for reduction of athletic related injury. Nearly all high school

and college football programs participate in some type of weight

training, speed, agility and conditioning regimens.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved