Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

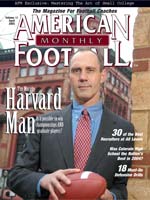

Redefining Murphy\'s LawIn eleven years as Harvard\'s head coach, every one of Tim Murphy\'s players have won an Ivy League Championship and, more importantly, all have graduated.by: David Srinivasan © More from this issue Harvard coach Tim Murphy is enjoying rare success despite dealing with handicaps many Division I coaches might bristle at facing. He works at the nation’s oldest college, one of the world’s elite educational institutions, so Murphy and his teams must live up to traditions nearly as old as America itself. He must also recruit student-athletes who can handle academic standards that might appear impossibly high. In addition, Murphy has zero athletic scholarships to offer his players.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved