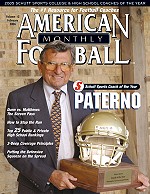

AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

Heart of a Lion: Joe Paternoby: Steve Silverman© More from this issue Football is a funny business. It is a war-like game in which the biggest, strongest and toughest will often come out on top. Throw in the elements of brains and intelligence and it can either amplify the preceding characteristic or eliminate it. The teams on the sidelines – on a given autumn afternoon or evening – want to humiliate, eliminate and defeat their opposite numbers. It is the most competitive of all sports. Yet there is a fraternity among its players and coaches that often belie the traits mentioned above. Make nice conversation with your enemy in the winter and you may be welcomed with open arms. Take the Penn State coaching staff. After suffering through a fourth losing season in the previous five years, Joe Paterno, offensive coordinator Galen Hall and quarterback coach Jay Paterno want....The full article can only be seen by subscribers. Subscribe today!

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved