Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

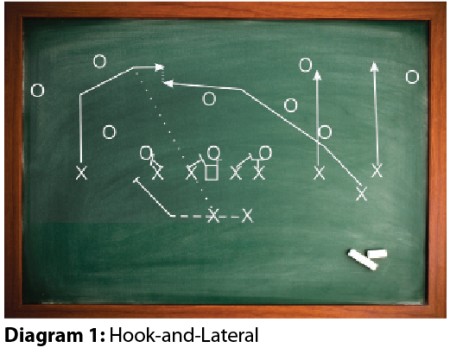

Trickeration: The Art of Deceiving a Defense. When And How To Use Trick Plays.by: David Srinivasan© More from this issue It was January 1, 2007 and the Boise State Broncos were reeling. Oklahoma’s 25 unanswered points gave the Sooners a 35-28 lead. The Broncos found themselves at 4th-and-18. Their season would end in 18 seconds. That’s when head coach Chris Petersen and OC Bryan Harsin reached into their gadget bag. Oklahoma scored on its first OT possession, a 25-yard run by Adrian Peterson. The Broncos got the ball, but....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved