Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

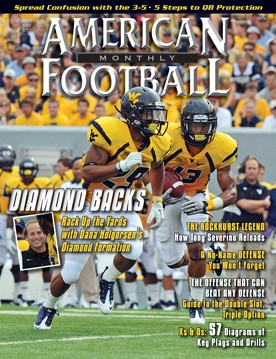

Diamond Backs – For a team with many playmakers, the Diamond formation may be the best way to showcase their talents.by: David Purdum© More from this issue In April, after a West Virginia spring practice, a few Mountaineer defensive coaches strolled over to running backs coach Robert Gillespie with troubled looks on their faces. They had just been introduced to the new facets of the Mountaineers’ already-potent three-back Diamond set Head Coach Dana Holgorsen and Gillespie had been installing. The defensive coaches’ initial reaction was shock. They said, “Man, that’s very tough to deal with,” Gillespie recalled. “They talked about how much they were going to have to work with the safeties on different run fits. And the thing that they really had problems dealing with was having their corner out there on an island against our best receiver, while the safety’s in the box. They said, ‘this is going to take some time to game plan for.” Clemson had close to a month to prep....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved