Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

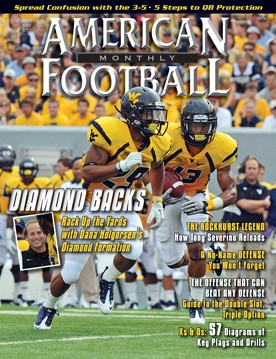

The Double Slot, Triple Option Offenseby: Ric JohnsAssistant Coach, Belleville East High School (IL) © More from this issue This offense, with simple option, counter option, read and play-action passes can be effective against any defense. In 1991, I made the decision that our team would transition into a double slot, triple option offensive program. Despite the fact our program was thriving, I felt that if we ever wanted to establish ourselves as an elite program, we needed an approach that would allow us to compete with the superior talent we would see deep into the playoffs. I began the transformation process by accumulating as much information as I could on double slot, triple option football. I focused on the service academies – Army, Navy, and Air Force were all running triple out of the double slot formation at the time as were Georgia Southern and Southwest Missouri State. When I felt comfortable in my understanding, we committed to ....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved