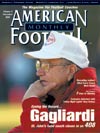

AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY THE #1 RESOURCE FOR FOOTBALL COACHES

Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

Past, Present, FutureAfter 49 stellar years, John Gagliardi takes aim at Eddie Robinson\'s record 408 wins.St. Cloud Times © More from this issue ďI donít have all the answers. As soon as I retire, then Iíll have all the answers. Iíll stay up in the stands with the rest of the fans who have all the answers, and I can answer it all then. Right now, I still have to go do it. Itís never easy to go out and get it done.Ē - John Gagliardi SO HOW MUCH LONGER IS JOHN GAGLIARDI GOING TO keep coaching? Itís a question the St. Johnís University football coach gets so often, he actually has developed two answers Ė one designed to draw laughs on the lecture and interview circuit, the other more matter-of-fact.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved