Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

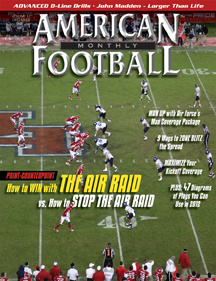

Point Counterpoint - Stopping the Air Raidby: David Purdum© More from this issue Spread Stoppers - Defending the Zone Read, Bubble Screen and Four Verticals Trying to defend the spread includes being creative and mixing defenses but pressure on the quarterback and aggressive open-field tackling are critical. The evolution of the spread offense has defensive coordinators longing for the good old days when defending the triple option meant accounting for the fullback, quarterback and a pitch man. But these days the third option might just as easily be a wide receiver on a quick bubble screen or even a slanting wide out that can really have your defense spinning. Welcome to the modern spread, an offense that has evolved to the point where defensive schemes are almost irrelevant. Instead, stopping a balanced, multi-faceted spread offense featuring a dynamic dual-threat quarte....The full article can only be seen by subscribers.

|

|

|||||||

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved